On the Organ Trail: Ethical Concerns with Donor Autonomy and Living Directed Donation

By: Aya Sugai-Munson

Nov. 21, 2024

In December 1954, Dr. Murray completed the first human living kidney transplant, a landmark stride in medicine. Decades later, he reflected on the profound ethical implications that operation surfaced saying he worried about “taking a normal person and doing a major operation not for his benefit but for another person’s” [1]. As medical advancements within organ transplantations multiply and evolve, ethical concerns have also developed. With 20 people dying every day waiting for a transplant, who deserves to live? To die? [2] As the social media age erupts, websites are beginning to allow donors to scroll through possible recipients, much like one might scroll through dating apps. This raises critical ethical questions surrounding organ transplants about how much autonomy donors should have in deciding the recipient of their organs.

Within the scope of organ transplants, there are living donations and deceased donor donations. The large majority of living donations are kidney and partial liver transplants. While deceased donors give consent before their death, living donors are knowingly parting with vital organs. Currently, the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act permits organs to be gifted to a specified recipient by the donor or donor’s family when the recipient is either emotionally or genetically related [2]. Within living donations, there are three categories: directed donation, kidney-paired donation, or non-directed donation. Directed donations are only allowed to a biological relative, close friend, or “a biologically unrelated person who has heard about the transplant candidate’s need,” the third in which the guidelines are clouded and uncertainty arises [4]. The kidney-paired donation, while less common, occurs when a transplant candidate wants to donate a kidney to a family or friend but is not a match. The transplant can still be made possible by another pair who do have matching blood types “swapping” donors, so each recipient receives their organ. With the increasing demand for organs each year and the daily addition of individuals to transplant lists, evaluating the ethical guidelines is vital to ensure that each patient is given equal opportunity at a life-changing procedure. While the current system for organ transplantations prioritizes recipients only on medically relevant criteria, directed donations could motivate donors who want to ensure their vital organs are sent to socially “worthy” and non-self-destructive individuals. However, allowing living directed donations entails many risks further marginalizing minorities across race, gender, and other groups failing to obtain organs in a just and unbiased manner. Transitioning from blind donations to allow living directed donations may motivate certain people to become donors and potentially expand the donor pool. However, an unbiased distribution with a robust adherence to purely medical criteria remains the only way to prevent violations of ethical principles and ensure fair and equitable allocation of life-saving organs.

As there are currently 112,402 people on the waitlist and only 3,312 total donors as of February 2020, increasing the donor pool through directed living donation is vital as it provides more flexibility and autonomy in the donation process [5]. From a utilitarian perspective, it is vital to take any measure to increase the pool of organ donations to save more lives. A spokesman for UK Transplant has said that only half the people who have stipulations for their organs—no alcoholics, smokers, or ethnic minorities—agree to join the donor list anyway. Given the extremely scarce supply of organs, it is important that organs be allocated to positive members of society that the donor approves of. A person should be able to donate their organs to those who share the same beliefs, just as one is able to hand down their property or money after their passing. This “opportunity to memorialize their lives and those of their family members by recognizing and honoring their personal values through the choice of recipients could motivate the donation” [6]. With more incentive to register as a donor, not only would the donor pool double, but the overall likelihood of a donor matching with a patient would increase, ultimately saving more lives.

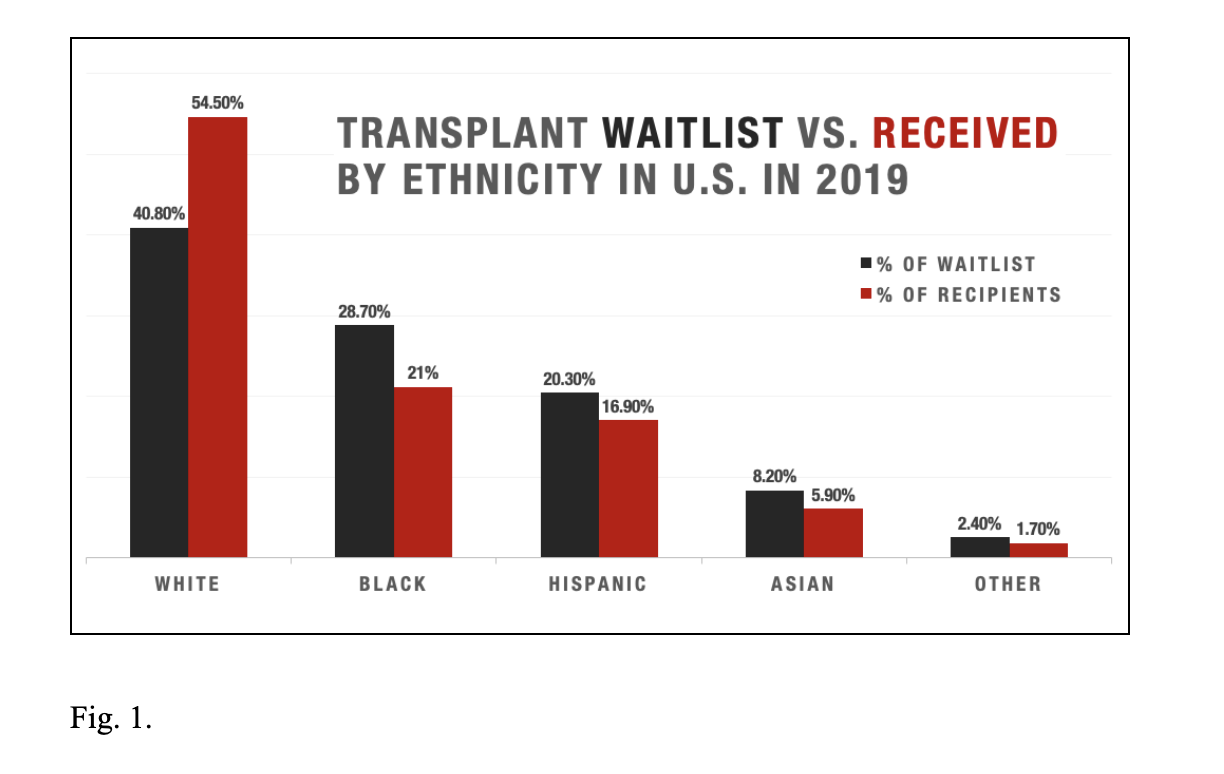

While allowing living directed donations between biologically or emotionally unconnected donors and recipients may increase the pool of organ donors, opponents of directed living donation argue that allowing the general public to select “worthy” applicants exacerbates discrimination. The idea that allowing donors to choose their recipients would significantly increase the donor pool and thus positively impact society is overoptimistic and flawed. In the past, moral problems with directed donations have caused uproar and protest from the public. For example, in 1998, a transplant center in the UK accepted an organ from a member of the KKK with the stipulation that it could only be donated to a white person [6]. With such events, the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) declared that “donation of organs in a manner which discriminates for or against a class of people based on race, national origin, religion, gender, or similar characteristics is unethical” and would not be accepted by transplant professionals [6]. However, the unconscious bias of doctors and physicians already causes certain minority groups a significant disadvantage in terms of receiving organs. In 2019, African Americans made up 3 in 10 candidates on the organ waitlist, but only comprised 21% of transplant recipients as seen in Figure 1. The key observation is whites were the only demographic receiving a disproportionate number of organ transplants relative to their representation on the waitlist.

Systemic racism bleeds into the medical system and continuing to allow directed living donation to random members of society would add yet another hurdle. While UNOS has strict regulations on racial discrimination, minorities still experience disparities in healthcare as doctors’ biases and stereotypes affect patient care. With the growing power and influence of social media, patients can and do advertise themselves on virtually any platform: Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, as well as designated transplant websites. If ordinary people, not under an oath to “do no harm,” were to have the liberty to select their recipients, these disparities along racial lines would intensify and a multitude of others would likely be created concerning gender, sexual orientation, age, and religion. Due to racism, the number of black recipients could further decrease. Due to sexism, the number of women recipients could decrease. Those who believe that queer individuals go against their religious beliefs would not choose members of the LGBTQ+ community and may choose those within their religion. This risks reinforcing the bias that a very specific margin of people, predictably white, cisgender, Christian males, deserve life-saving transplants, while others do not. Bringing in nonmedical criteria as the largest factor in determining who lives and who dies would undoubtedly lead to greater disparities; a truth that ethically cannot be overlooked. In a society that strives for equality, it would be unethical to partake in racist, sexist, or similarly prejudiced actions. “When the gift is valuable and may concern life or death, a purely egalitarian distribution is the best defendable position,” says Guido Pennings, a Professor of Ethics and Bioethics at Ghent University. While directed donations to family and friends are morally permissible, donors selecting non-related recipients becomes a beauty contest where organs must be “applied” for rather than given to the most medically deserving person. As social media’s influence expands, directing donations through methods of selecting recipients on their platforms has become a greater risk. These methods go against the altruistic intents of organ donation and are inconsistent with an equality-seeking society. Since 2004, directed donations via websites such as matchingdonors.com, a website that still exists today, have made it possible for organ donors to browse potential recipients, complete with a photo and captivating story, and choose a candidate for their organ. Patients can promote themselves through videos, stories, bios, photos, and more, explaining why they deserve the donation. While this may increase interest in donating an organ, it also becomes a sort of “beauty contest where patients with the most heart-rending story are most likely to receive transplants” [7]. This creates an imbalance where organs are going to the story that best pulls on heartstrings, rather than someone who is in more critical condition or is in greater need. As people are easily swayed, recipients may also exaggerate their condition to make it seem bleaker than reality. Additionally, whether a person donates or not should not depend on whether or not there appear to be promising recipients on a website, but should be in accordance with the wait times under the jurisdiction of UNOS.

Those in favor of directed donations argue that they should be able to choose to whom their organs are given because they do not want the lives of some members of society such as drug users to be saved. Current registered donors should be prioritized in the selection of organ allocation because this eliminates the risk of “free riders.” The shortage of organs increases every year as the waitlist grows, and on average 20 people die everyday waiting for a transplant [1]. While “donation rates have increased by only 3% each year from 1994 to 2003,” the waiting list has grown by 490% from 1991 to 2018 [8,9]. Due to the scarcity of organs relative to the tremendous need, opponents argue the most deserving people who benefit society should be given a competitive edge over those who are not willing to donate an organ themselves. Organs for transplant surgery are still in limited supply despite medical advancements and thus are “not a human right,” and so “viewing free riders as having lower priority in organ allocation is ethically permissible” [8]. This approach emphasizes the duty of the citizen to give back to their community in case of their death, and the individual reaps the reward for their humanitarian choices. By prioritizing those who choose to give back to their community, the most generous members of society would have higher priority and a higher probability of having their lives saved. This is not an altogether new idea, as preferred status for those registered as organ donors already exists in countries such as Singapore. In 1987, Singapore passed the Human Organ Transplantation Act (HOTA), stating that any patient over the age of 21 would have their organs donated after death in order to increase the pool of organ donors. Those who opt-in under HOTA have higher priority if they require an organ transplant in the future. Citizens can choose to completely opt-out or select specific organs they are willing to donate [10]. This method of prioritizing current donors would be a logical way to incentivize more people to register as donors as well as focus recipient priorities.

Although proponents of directed donation support equal priority – in part because not all those needing vital organs can donate themselves due to religious convictions – critics believe in giving higher priority to donors. One leading organization of organ transplantations nationwide, UNOS, expressed concern in 1993 that giving preferred status to those willing to be organ donors would create a parallel between organ donor status and moral worthiness. Within the context of religion lie contradictory views from the medical community and religious law. Israel, a historically religious land dominated by those of Jewish faith, has extremely low numbers of organ donors. This is no fault of the individuals born into this faith in this country. Seen as disrespectful and sacrilegious, “the law enshrines religious discrimination, since Haredi patients decline to donate based on their religious beliefs” says Danielle Ofri MD, a clinical professor at New York University [11]. The idea of allowing one’s own body to be “desecrated” to donate organs is sacrilegious to many Jews, and many are thus opposed to organ donation. Within Islamic law, similar conflicts arise as Shari’a law states that there are two categories of human rights. Huquq-Allah, the rights of God, and Huquq al-Ibad, the rights of the individual [12]. Muslims believe that they do not have ownership over their body or spirit, but that these are God’s gifts. Thus, donating organs is not within the individual’s right. Similar to Judaism, desecration of the dead is opposed in Islamic culture as well, similar to Judaism. However, conflict arises from clashing opinions among Islamic leaders, causing differing takes on Islamic laws concerning organ donation. Confusion and a lack of one definitive law regarding organ donation cause negativity towards what is traditionally considered in America to be a noble act. However, as religious interpretations vary, asking one to oppose their religion to get an equal chance at an organ is unprincipled.

Beyond concerns of inequity caused by religious affiliations, problems also arise from diseases such as alcoholism, a factor that has been long disputed in the transplant community. Opponents of blind donation underline that alcoholics needing transplants for their self-inflicted illnesses should be given lower priority as they both actively contribute to their disease and would also damage the transplanted organ. Currently, transplant hospitals commonly require alcoholics to commit to a period of six months of sobriety before they can join the transplant waitlist. This rule is vital to the protection of the scarce supply of organs as the six-month rule reduces the occurrence of relapses in alcoholics. The percentage of alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) rose from 27.2% in 2010 to 36.7% in 2016, according to Norah A. Terrault MD at the University of California San Francisco [13]. With the increase in ALD, it is generally assumed that the number of liver transplants going towards ALD patients would increase proportionally. Instead of allocating more than one-third of the available livers for donation to those with alcohol cirrhosis, these livers could go to individuals who suffer from liver disease that are not self-inflicted. Additionally, while ALD and non-ALD patients have similar survival rates up to 5 years, rates beyond this benchmark are 11% lower for ALD patients [14]. The waiting period of six months thus decreases the risk of the organ failing, and therefore should be required for ALD patients to optimize survival.

Specifically looking at medical criteria, those with ALD and low predicted chance of relapse should be given the same priority as other organ recipients as they have a negligible difference in survival rate post-op. Primarily, discriminating based on whether a disease is alcohol-related risks causing inequity between patients, especially when determining if continued drinking habits are a choice. According to a 2008 study conducted by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, genetic factors account for 40-60% of the underlying causes for alcoholism [15]. Beyond genetic factors, Brian P. Lee, MD, MPH, a gastroenterology and hepatology fellow at UCSF argues that a change in national policy is due as external factors such as “patient’s geography and the transplant center’s policy on alcohol abstinence prior to transplant” can cause potential inequity in care [14]. ALD is also the most common reason for liver transplants in the US and is “implicated in 48 percent of liver-related deaths, which remains higher than its proportion of liver transplants,” meaning a policy change would lead to more lives saved [14]. Additionally, Johns Hopkins conducted a study from 2012 to 2017, testing the survival rates of patients without the six-month sobriety rule compared to those with it. The results of both were statistically identical: 28% relapsed at one point and 98% of all patients were sober by the end of the study. Throughout this study, John Hopkins additionally developed a new technology called “SALT,” Sustained Alcohol use post-Liver Transplant which showed to be 95% effective in predicting a patient with ALD’s risk of alcohol use post-op. SALT measures four variables associated with sustained alcohol use to predict the likelihood of relapse [15]. In a 54-day test with 134 liver transplant recipients, 74% were abstinent and 16% had slip-ups only. The objection given to allowing alcoholics to be given the same priority as others is often that they will simply return to their habits and consequently damage their transplant organ, ultimately wasting an organ. To prevent this, SALT can be applied to all ALD cases in giving priority to those who have a lower risk of returning to sustained substance abuse.

Another form of substance abuse, smoking and other types of tobacco use, however, have drastically different consequences on a potential recipient’s organs and systems. The disastrous effects of tobacco use on the organs on donors as well as for recipients are so significant that it is morally permissible to give lower priority to these donors and recipients. Smoking affects a larger body of organ systems than that of drinking and “significantly increases the risk of cardiovascular events (29.2% vs. 15.4%), renal fibrosis, rejection, and malignancy (13% vs. 2%)” [17]. Current smokers not only have a 260% increase in chance of death after kidney transplant compared to non-smokers, but the risk of cardiovascular death is also increased by 60% [18]. Recipients of smokers’ organs also have a higher mortality rate and are at a greater risk for intensive care and ventilation post-op. The risk involved with using compromised organs or donating to compromised individuals outweighs the consequences involved with further reducing the organ donation pool. The negative impact of smoking thus calls for a six-month abstinence period in the case of lung, heart, or other transplants. This is directly caused by the patient’s lifestyle choices. Allowing directed donations, while potentially increasing the pool of organ donors would exacerbate discrimination because allowing the general public to select worthy applicants would cause the violation of current equality guidelines.

The ethical dilemmas concerning organ transplantations are of critical importance as they weigh the value of an individual’s life when nonmedical criteria are manipulated and brought into the equation. Data suggests that racial and other biases skew the distribution of life-saving organs, primarily when giving priority to nonmedical criteria. Due to this, living directed donations tend to exacerbate inequitable allocation across a wide spectrum of factors, some biologically inherited and others self-inflicted, unraveling efforts toward fairness and equality. For the purposes of advocating for equality, the determination of who should receive vital life-saving organs should solely be controlled by UNOS under objective medical guidelines. These include biases against substance use, religious considerations, and ingrained systemic racism. The responsibility should not lay in the hands of individuals, potentially swayed by racist, sexist, xenophobic biases, whether purposeful or unconscious. In these life-or-death decisions, science should have the final word.